Another Get-a-Life Tree Activity

This past weekend began on Friday at 11 a.m. when I logged onto a Zoom workshop hosted by Kate Hill. It was to be the beginning of nearly 8 hours of “making basic French cured meats at home … using primarily pork.” During the workshop, comprised of two hours on Friday, two and one-half hours on Saturday, and three and one-half hours on Sunday, Kate shared some of her favorite simple skills that produce safe and time-honored French-style deli meats to enjoy at home, from lardons to Saucisse de Toulouse, country-style pâtés to a peppery filet sec, all perfect for home-made charcuterie plates.

If I had to narrow my choice of meats down to one for the rest of my life, I am quite certain that meat would be pork.

James Beard

But before I get ahead of myself, let me start with the ingredients that had to be assembled before the workshop began. As mentioned above, the focus of the weekend was on pork, and lots of it, including: a 4-pound pork belly, 2 pounds of pork tenderloin, 4 pounds of pork shoulder, and 2 pounds of pork trim. In addition, I needed to locate 1/4 pound of liver (beef had to do for this as pork liver could not be reasonably found) and natural hog casings to make sausage. Thanks to a special order with the local butcher and a few things from Amazon, I had all of these ingredients in hand by Wednesday. In addition to the meat, a few pantry items were required, including lots of sea salt, lots of black pepper corns (to be ground), onions, potatoes, flour and butter. With these ingredients, our handy Kitchen Aid meat grinder/sausage stuffer, and kitchen scale in hand, I was ready for the challenge of the weekend workshop.

After a good dinner one can forgive anybody, even one’s own relations.

Oscar Wilde

Friday involved learning about safely handling raw meats and working with dry-cured whole muscles. Specifically, we were going to create rolled pork belly, or Ventreche, and dried pork loin, or Filets Secs. We began by trimming the pork belly to remove excess connective tissue and to “square it up” to facilitate rolling it up like a jelly roll on Sunday. Similarly, we trimmed off the smaller ends of the pork tenderloin to ensure a consistent diameter. After these steps, we applied salt equal to 3% of the weight of each cut of meat. The salt is rubbed in on all sides and edges of the pork belly and tenderloins. The cuts of meat are then allowed to cure for 24 hours in an open bin in the refrigerator. By allowing them to sit, the salt works its way into the meat, drawing out some of the moisture and making the meat firmer.

We then adjourned until 11 a.m. on Saturday, at which point we again began with instruction on how to handle meat safely, particularly when using a grinder and sausage stuffer. We then prepared our meat grinders for the upcoming task of making Saucisse de Toulouse. Per Kate, “[b]y law, Saucisse de Toulouse is defined very rigorously and the basic recipe is a national law to be respected including the geographic location of the pig, natural casings, amounts of lean meat to pork fat, and absence of all preservatives and additives.” The most basic of all fresh charcuterie, this sausage is the foundation of may Southwest French dishes including cassoulet. The sausage must follow the following proportions: 80% fresh pork shoulder and collar, and 20% fat. For every kilogram of ground pork, 14 grams of milled sea salt (so, 14% by weight) and 2 grams of freshly ground black pepper (or 2% by weight). We cut the pork up into cubes of meat that would fit into our grinder, seasoned the meat with the salt and pepper, and began running the meat through. For this sausage, a grinder plate with holes from 8 to 10 millimeters in diameter produces the proper coarseness of the ground fat and meat.

Once all the meat is ground, the casings are prepared by cleaning them and inserting them over the stuffing tube attachment of the stuffer. We then fed the ground meat through the stuffer and into the casings, slowing holding the casing as it slid off the stuffing tube to ensure a consist thickness of the sausage.

On Saturday we also rubbed the excess salt (of which there was very, very little) off the pork belly and pork tenderloins and returned them to the refrigerator so the salt would have 24 more hours to “equalize throughout the meat.”

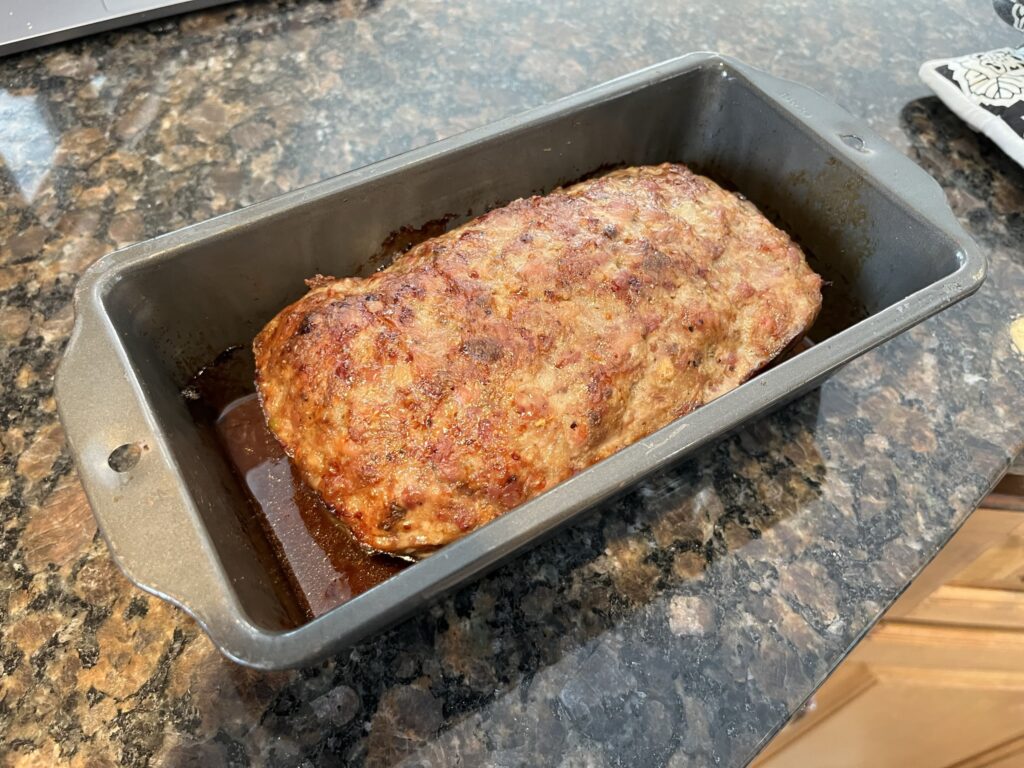

We adjourned until Sunday, when be began by preparing the meat and other ingredients for the pork pâté. Pork pate is not what many Americans envision as pate. It is not a paste-like substance, but is much more like meatloaf.

Boy, those French! They have a different word for everything.

Steve Martin

The pâté begins with whatever amount of meat you have left over from the other work you’ve been doing with pork. For purposes of example, let’s assume you have 1 kilogram (i.e., 1,000 grams) of pork trim. To the chunks of pork trim you add 100 grams of fresh blanched pork liver, 100 grams of onion chunks, and 100 grams of cooked potato chunks. After mixing this together by hand, you add 14% of the combined weight of all the ingredients (i.e., 1,300 grams above) of salt and 2% of the combined weight in pepper to the mix. You combine it all by hand and THEN run the mixture through the grinder. You mix it further with your hands until it becomes sticky, form it into a ball, and then transfer it to a tureen or loaf pan for cooking, being careful to remove any air pockets. The mixture is cooked in a 400 degree F oven until the internal temperature of the pâté reaches and maintains 160 degrees F. That’s it! The pâté is served by cutting it in slices and eating it on bread as a sandwich or with crackers on a charcuterie plate (or in whatever way you enjoy eating it!).

We reserved some of the pâté meat mixture so we could make small meat pies, sort of like a pâté empanada. First, we made a hot water pastry crust, the ingredients of which were 500 grams of flour, 150 milliliters of very hot water, 200 grams of butter or other fat, and 3 grams of each of sugar and sea salt. This simple crust recipe can be ready in minutes, and was used to enclose meatball-sized portions of the pâté mixture. I made my pies by simply pulling the crust around the meat mixture and pinching it together at the top. These tasty morsels baked in the 400 degree F oven until well-browned (approximately 30 minutes).

We closed out the workshop by finishing our pork belly and pork tenderloins. The pork belly was finished by rolling it up and tying it with string. The salt will continue to equalize in the meat, proving a consistent texture throughout. This Ventreche can be used in any dish in which you’d use bacon. It can also be cut into round slices and used on bread, or as lardons to provide fat and flavor for cooking. The tenderloins, because they are a much leaner cut of meat, will continue to lose moisture weight at a rate of approximately 1% per day for the next 30 days. At the end of that period, they can be sliced into small medallions. These small slices of meat will be very firm and serve as a very good meat with crackers and cheese.

Seize the moment. Remember all those women on the ‘Titanic’ who waved off the dessert cart.

Erma Bombeck

The workshop was thoroughly enjoyable, and I enjoyed learning from Kate and my twelve or so classmates from around the world!

And now the disclaimer: Any errors in the recipes, proportions, or processes are my own errors in translating the steps throughout the workshop and and are not those of Kate Hill. If you’re interested in learning more and participating in future workshops, visit Kate’s site at https://kitchen-at-camont.com.